As of this writing, I assume all 66 subscribers to this newsletter know me, whether in real life or through my book, my old blog, or social media in general. But you know me somehow. And if you know me, odds are you know about my admiration for Servant of God Nicholas Black Elk. The more I learn about him, the way he lived and joined both his Catholic faith and his Lakota identity, the more I’m convinced he’s desperately needed by the Church.

In 2019, the Vatican held the Synod of Bishops on the Amazon, which was intended to “identify new paths of evangelization of God’s people in that region”, with a specific focus on indigenous Catholics. The synod was marked by controversy straight out the gate. Well known Catholic news agencies reported on it using enough scare quotes in their articles to terrify the bravest of readers, and the tone of some reporting was breathtaking in its smug condescension toward indigenous cultures (“Putting people with university training on the same level as shamans is in itself problematic” is one of my favorite examples of this. The author goes on to make theological arguments against shamanism, but note that the first complaint was the audacity of valuing shamans as much as academics on the topic of indigenous culture). Other outlets went all in on the patently click-baity framing of events (notice the headline: “Ecological ritual” vs. the more neutral “indigenous performance” used in the body of the article) and guilt-by-innuendo reporting.

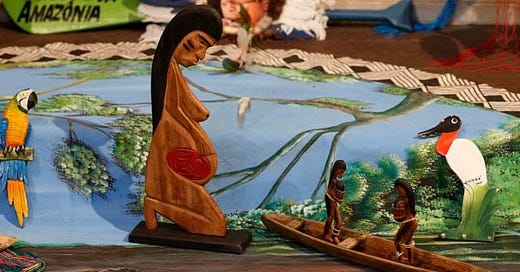

The fervor culminated with the theft and vandalism of five statues, stolen from a church just four blocks away from St. Peter’s, and subsequently thrown into the Tiber. This act seemed to sum up all the problems with the Synod in general, and in a broader scope, notions toward indigenous expressions of our universal Catholic faith.

I was asked to speak at the Diocese of Phoenix’s annual Women’s Conference early this year. It was my privilege to be given a chance to introduce Black Elk to a group of women who may not have known about the faithful catechist, responsible for bringing some 400 of his fellow Lakota to Christ. Afterwards, one of the attendees came up to me and told me the story of her relatives, members of the Apache nation living in New Mexico, who have been told over and over again, from Christian and non-Christian sources, that they cannot participate in both their culture and their faith. Close to tears, the woman told me how much she wished Black Elk was better known among her people, his life proof that Jesus doesn’t expect you to abandon your culture to become His disciple.

While I firmly believe that Black Elk’s intercession is a powerful bridge between the Sacred Heart and indigenous hearts, non-indigenous Christians must do our part. Our indigenous brothers and sisters have a place at the Feast of the Lamb, and they have riches to share with all of Christ’s Church, but as the events of the Amazon Synod showed, and as the Apache woman shared, there are deeply concerning obstacles that are preventing genuine welcome. This essay is certainly not going to solve all of them, but I do think it’s helpful to consider some roots of these obstacles by returning to my Bible Belt Protestant friends.

I look at resistance my fellow brothers and sisters in Christ have toward indigenous displays of the Faith, and, assuming genuine good intentions on their part, I apply the “two problems” I outlined in the previous post, and look at ways to address them.

Too Pagan. The first question we should ask ourselves here is “does this practice glorify or diminish Christ? Does it enhance our ability to follow Him, or does it lead us away from His rule? Is it contrary to the teachings of Moral Law?” Then after asking the questions, we need to find an authoritative source for the answers, and listen to their wisdom. This seems to be one of the biggest complaints critics had of the Amazon Synod- their questions about the meaning behind dances and gifts and imagery were either ignored, blown off, or directed to other sources who directed to other sources in a frustrating loop. Why Vatican officials didn’t allow their indigenous guests to explain the meaning behind the symbols was not only disastrous mystery, but it was in direct opposition to the stated aim of the Synod. Evangelization, after all, is never effective if it’s presented as a one way conversation.

This process is not a simple one, and it requires both discernment and humility. Discernment in knowing who is an authority on the issue, and humility in accepting the answer. We can’t just yell “syncretism” every time we experience foreign ways of worshiping God; we have to ask questions and keep asking until the answers come and our hearts are humble enough to listen.

Too Catholic. In this case, it’s more accurate to say “Too Indigenous”, but in either case, it’s a sense of Otherness that lies at the heart of resistance. Just like some non-Catholic Christians cannot bring themselves to consider Jesus’ mother as anything other than an ordinary woman because it’s too Catholic a thing to do, some non-Indigenous cannot bring themselves to consider Indigenous contributions to the Faith as anything other than “too Indian”. But I don’t think this is usually done out of malice.

As much as I hate the current cultural obsession with making everything about race, in the case of indigenous/non-indigenous relations, I think Americans and Canadians have crushing historical baggage to acknowledge first. There is not a single person alive today who is responsible for the atrocities committed by colonists and westward expanding settlers, but neither is there a non-indigenous North American who isn’t profiting in some way from that legacy of genocide and displacement. Add to the trauma soup the legacy of Church-run Indian boarding schools, with living survivors of those abusive institutions still among us, and I think there is a real temptation to try to diminish the guilt by diminishing the people. Indigenous expressions of Christianity are just “too other” to bother with all the historical injustice that comes with the territory.

So how do we face these two problems and move past them? The Church has clearly shown it could do it in the past. After all, our faith, which started in the Middle East, did not apostatize when it bumped into indigenous cultures in Northern Europe. It didn’t insist that these new Christians abandon their cultures and imitate first century Judea. Sure, there was a St. Boniface, whose destruction of the Donar Oak was, I’m sure, strong within the minds of the thieves who stole the Amazon statues from the church, but there was also a St. Patrick, who lived among indigenous Irish and used their sacred imagery in the service of Christ (shamrocks, anyone?). And legend has it that it was ol’ Oak Slayer Boniface himself who, pointing at a small fir revealed after the mighty oak was felled, gave us the first Christmas tree.

Logic and precedence tell us that Christ’s church only gets richer and more beautiful with the unique cultural gifts each nation, tribe, people and tongue bring.

My friend Damian Costello, who has written extensively about Black Elk and has been heavily involved with his Cause for sainthood, gave an example of this in passing in one of his recent articles. Writing about the breathtaking stained glass windows in St. Augustine Parish in Montpellier, Vermont, Costello says of the window titled “The Raising of the Cross”:

Workers raise the crucified Christ up with rope extended from the cross. Although almost certainly not intended by [the artist], this echoes the comparison that Indigenous Catholics of the Plains Tribes made between the Sun Dance and the crucifixion, sometimes using the phrase “Jesus was the first Sun Dancer.”

Briefly, the Sun Dance is an event designed to acknowledge, strengthen, and give thanks for relationship bonds, seek healing, and offer personal sacrifice for the well-being of the community. It was outlawed by both Canada and the US, in one of a series of attempts to suppress indigenous culture, and while such laws have since been overturned, clandestine Sun Dances continued regardless.

When comparisons like the one above, between Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross and the Sun Dance are made, it is a clear expression of a uniquely indigenous Christianity. And as the Dance is closed off to non-Indigenous, Indigenous Catholics are sorely needed in this context, a St. Hubert in the Ardennes, bringing Christ with an indigenous face. Yet where do these faithful Catholics come from, if they are told that they cannot be both indigenous and Christian? To be clear, this sentiment flows two ways, from non-indigenous Christians to native peoples, as well as from tribal sources to native peoples exploring the Faith. As I am not indigenous, I don’t have the authority to speak to the later, and can only attempt to address the former.

The Quinceañera* is an example, maybe, of what this could look like. The coming of age ceremony has its roots in the cultural practices of the Incas, the Aztecs, the Maya and the Toltecs. And while the interactions between these indigenous groups and the Spanish were marked by genocide and bloodshed, Christ’s grace still managed to take root. What was once a pagan celebration of the entry into womanhood became an opportunity to renew a girl’s baptismal promises, to identify faithful spiritual mentors, and reinforce the dignity given to every woman as a beloved child of God.

Another example of indigenous expressions of Catholicism that appears to becoming more common among non-indigenous is the Ofrenda built for All Souls Day. What Leila Lawler’s book The Little Oratory did to popularize domestic altars, I think maybe Disney (of all sources! Disney!) did for the focus of those home altars during November. Marigolds and old photographs on people’s prayer spaces have been steadily increasing on social media, and while on surface this seems terribly, well, surface, I think it also speaks to a level of comfort and familiarity the dominant culture is feeling with some indigenous expressions of the Faith.

The bloodshed, betrayal, and bad faith that have historically marked Indigenous and white American interactions need to be addressed and acknowledged, and that cannot effectively happen without grace pouring down in waves. Cartoon ofrendas and Quinceañeras, like Christmas trees, can be written off as surface things, rife for commercialization and consumerism, but they’re also examples how indigenous practices offer richness to our Faith. Making space at the table for indigenous expressions makes space in our hearts for Christ’s grace, and that’s where forgiveness and wholeness lies.

Throwing statues into rivers and attempting to cut cultural expression off from religious observance is just as contrary to evangelization as is ignoring good faith questions and pretending differences don’t exist. Good communication is needed as much as good listening, and people like Black Elk to help us facilitate both.

Servant of God Nicholas Black Elk, pray for us.

________________________________________________________________

*though, judging by the massive industry built up around the modern quinceañera, maybe this is a terrible example and the thought of such a deeply spiritual event becoming commercialized might be doing my argument more harm than good.

Cari, this is absolutely spot-on and beautifully said. Introducing this painful issue of Christian cultural isolationism with the adoption of the Christmas tree is so, so poignant. St. Paul summed it all up so well in Galatians, yet somehow the same old problems keep cropping up. There's so much beauty in the grafting of regional culture with Christianity, and a stark disservice has been done by trying to put a wedge between them.

I have a lot of questions about this topic.

I do not have a problem acknowledging the many, many issues that European settlers caused when they came to the Americas. I don't have a problem discussing how the sins committed by these people still cause roadblocks for conversion for Native peoples today.

But the Amazon Synod gives me great, great pause. I'm willing to entertain the idea that certain ceremonies or rituals weren't explained well - and I would really, really like to hear those explanations! But there was a lot things happening there that really did seem like idolatry. Were those statues the Amazon goddess Pachamama? That is how the Pope referred to them. The Vatican denied they were the Blessed Virgin, but wouldn't explain what they were!

This entire incident was centered within a papacy that is riddled with problems in providing moral guidance, even on issues that are clearly settled church teaching. So it makes sense that a cloud of suspicion followed these events - and since then, we've certainly had no indication that our Holy Father would have any problem actively promoting a practice that would be contrary to the faith, since he systematically refuses to clarify any action or words of his which cast doubt on Catholic beliefs and morals.

Honestly, I think it's difficult to place people's reactions to the Amazonian Synod into a category unaffiliated with people's deep anger at Pope who refuses to be a shepherd.

Most people are unfamiliar with indigenous practices - unfamiliar and uninterested. A discussion of what they are, and how they can benefit the entire Church, is a conversation worth having.